#6 - Who's Being Sensitive?

Why the world needs both Sitters and Roamers

At a Glance

What is a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP)?

Advantages and challenges for HSPs

Guess who’s highly sensitive?

Public speaking: is it fear or just overstimulation?

Spend any time researching introversion, and you'll soon come across the concept of high sensitivity. While the term might evoke images of Victorian fainting couches, tortured artists, and reclusive hermits (and no doubt these were sensitive souls) the truth might surprise you: it's far from a fringe phenomenon.

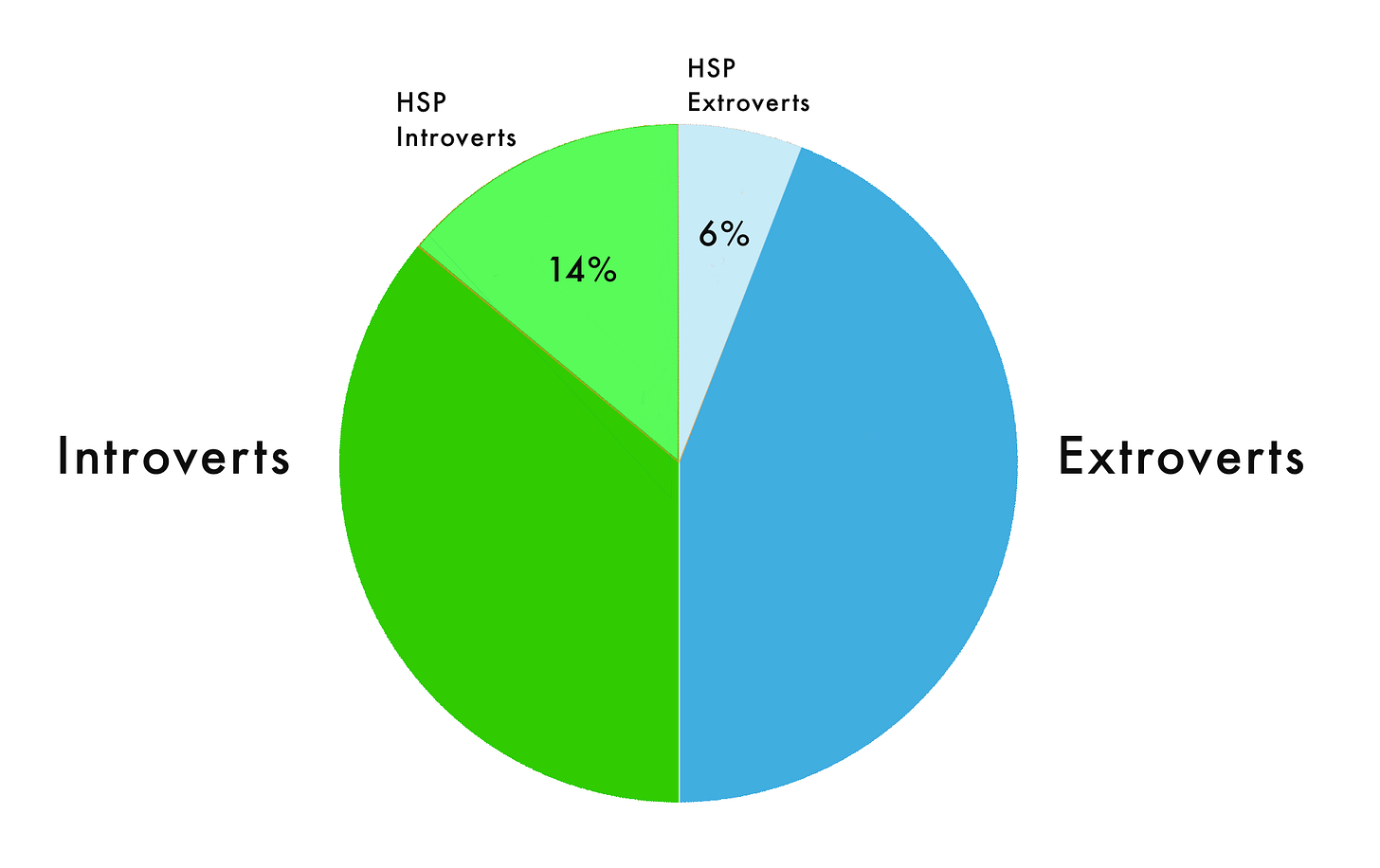

A full 20% of the global population can be classified as Highly Sensitive Persons (HSPs)—that’s over 1.6 Billion people based on current statistics! Which is a lot of sensitive people!

What’s more, high sensitivity is not exclusive to introverts: studies show 30% of HSPs are extroverts. It’s is a distinct trait, separate and independent from introversion.[1]

What is High Sensitivity?

High Sensitivity refers to the unique way some of us processes sensory input. HSPs experience it more deeply, paying heightened attention to their environment, sensations, and emotions.

What's more, scientists have identified forms of high sensitivity in over 100 species, with a comparable distribution of around 15-20% of the population![2]

With such a widespread pattern, scientists argue that this serves as strong evidence that having a segment of the population more attuned and responsive to its environment provides clear evolutionary advantages.

Here’s how that works.

Sitters vs. Roamers

Take fruit flies as an example: researchers have classified them into “sitters” (15%) and “roamers” (85%). Roamers are the ones you’re most likely to notice, constantly moving in search of food, while sitters frequently pause to take in more of their surroundings.

It turns out that these sitters possess greater neural complexity than their peers, enabling a deeper processing of sensory input.[3] They are more attuned to changes in their environment—such as shifts in light, temperature, or the approach of hazards—and respond accordingly, which can boost their chances of survival in specific situations. In essence, sitters are the HSPs of the fruit fly world!

Scientists see these variations in sensitivity as complementary survival strategies. A population thrives by balancing both types: it wouldn’t work if everyone were highly sensitive. At certain times, we rely on the bold roamers to discover new resources, while in others, it’s the observant sitters—who pause to deeply notice and feel their environment—who help ensure survival.

This same trait has been observed in sunfish (with the bold ones falling into traps purposely set by scientists, while the cautious ones remain safe), in Rhesus monkeys, and, of course, in humans!

Sensitive Humans

Dr. Elaine Aron was the first to identify and systematically study this trait, and she has done more than anyone to advance our understanding of what it means to be highly sensitive.

Among humans, “sitters” and “roamers” align, in Dr. Aron’s view, with the “warrior” and “priestly or advisor” classes that evolved in Western civilization. Just as bold warriors were essential for leading the charge, perceptive and thoughtful observers played a critical role in shaping strategy and finding the best ways to prevent or resolve conflict.

HSPs notice more, and can therefore make deeper connections than others. Many creatives are HSPs: artists, writers and musicians, of course. But that same sensitivity—otherwise known as situational awareness—can be a great advantage in leadership.

For Aron, high sensitivity is defined by 4 key characteristics, captured in the mnemonic DOES.

D - Depth of Processing: a deep engagement with sensory stimuli, including sights, sounds, smells, noise, and emotions.

O - Overstimulation: as the result of intense sensory processing, particularly in crowded, noisy, or confrontational environments.

E - Emotionally Reactive and Empathetic: stemming from a heightened sensitivity to and deep processing of others’ emotions.

S - Sensitivity to Subtle Stimuli: granting the ability to perceive and draw connections that might go unnoticed by others.

Aron’s book The Highly Sensitive Person covers the research behind this trait, but, above all, serves as a handbook—an owner’s manual—for anyone navigating life with an HSP’s body and temperament. For a great summary, check out the one-hour documentary Sensitive on Amazon Prime Video. If you’re curious whether you might be highly sensitive, you can take a quick self-test on Dr. Aron’s website—it takes less than five minutes!

Advantages and challenges for HSPs

Aron demonstrates that, in most cases, being an HSP is an advantage. Among the four key characteristics, it’s only overstimulation that poses challenges—such as feeling overwhelmed in crowds or noisy parties—and requires active management by the HSP.

Overstimulation can significantly impair overall performance, because your thinking, verbal abilities, and situational awareness may decline dramatically as a result of flooding. With self-awareness, HSPs can recognize these situations and manage them, with preparation, active calming techniques, by stepping away when needed, and by organizing their lives to minimize exposure to such scenarios whenever possible.

Research in HSP children shows that high sensitivity can result in either significantly better or worse outcomes, depending on the quality of parenting and environment a child experiences. High sensitivity functions as an amplifier of a child’s experiences, making HSP children “more susceptible” to environmental influences.

HSP children with supportive childhoods tend to be more resilient and successful compared to their non-HSP peers.

However, HSPs who experience poor childhoods often fare worse than their non-HSP peers, as they are more deeply affected by parental neglect. This heightened impact can lead to issues such as neuroticism, anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.

On the flip side, all HSPs—regardless of their childhood experiences—are more receptive to interventions, making them significantly more likely to benefit from treatments or practices aimed at helping them overcome their past. In general, HSPs are highly adaptable and tend to gain more from self-improvement techniques than the rest of the population.

Guess who’s highly sensitive?

It’s taken me time to recognize and embrace my introversion—to accept that I need alone time to recharge, that I value deeper connections with a few close friends over a large social circle, and that I often “run out” of energy in loud, complex social settings like conferences or all-day meetings.

But some things still didn’t add up. Introversion couldn’t fully explain certain contradictions in my nature—like how I genuinely look forward to and enjoy public speaking, yet still feel a wave of nerves every time I begin—even if I’ve felt completely calm up until that moment. I’ve spoken to audiences of 1,500 people, yet speaking to a group of just 20 triggers the same reaction. The amount of rest or a recharged social battery has no bearing on it. I seem to be hardwired for this reaction. I sensed something deeper was at play.

It was when I read about overstimulation that everything started to make sense. Maybe my nervousness wasn’t rooted in fear anymore. Maybe it was just overstimulation.

I took the self-test, and lo and behold—guess who’s highly sensitive?

Looking back

I learned early on that being sensitive was seen as a liability.

Watching my father dismiss my mother’s feelings with “you’re so sensitive” and seeing her pained reaction, I internalized the message that sensitivity was weak, inferior, and unsafe.

As a sensitive boy, this posed major problems. Temperamentally, I was like my mother, betrayed time and again by tears—whether it was losing a game of chess to my father, or getting a bloody nose from a baseball playing catch. My sensitivity made me an easy target for bullies in the early primary grades, both on the bus and the playground.

This landed me in a Karate class, where my parents hoped to toughen me up. Run by an old Marine with a buzz cut in the basement of our local YMCA, the sensei lined up our group of 7-to-9-year-olds and “taught us” to take a punch with a brief instruction: force air rapidly out of your lungs and brace just before impact. Then proceeded to walk the line, punching each us in the gut. That was my last such class (my mother is still traumatized).

My parents, of course, cared deeply about me and for each other. It was the 1980s—a time when Sylvester Stallone’s violent Rambo and Rocky characters dominated pop culture, and Ronald Reagan’s aggressive stance was believed to help win the Cold War. Sensitive men like Jimmy Carter were often ridiculed. My parents did their best to prepare me for this world.

I managed to navigate all of this—successfully, at least in my own mind—by repressing my sensitivity and conforming to societal expectations. However, the cost was steep: occasional bouts of depression, years of anxiety and low self-esteem. Yet, I’m grateful for this struggle, as it ultimately led me down the path to rediscovering my authentic self.

Public speaking: is it fear or overstimulation?

Looking back, everything makes so much more sense. Being highly sensitive provides a far better explanation for many of my challenges, including public speaking. I genuinely love public speaking—sharing my thoughts, connecting with others, and making people laugh. Yet it often makes me nervous to some degree, and occasionally that nervousness impacts my performance. Other times, the feelings are so subtle they barely register—or don’t appear at all.

If I’m well-rested when I speak, I have plenty of “social energy,” yet this seems to have no effect on my performance. Introversion alone doesn’t account for this challenge—or for any specific fear of public speaking. Being highly sensitive does.

This is a textbook example of the HSP tendency to become overstimulated. As stimuli increase, HSPs can easily become over-aroused, which can ultimately impact their performance. Getting up to speak in front of a group certainly qualifies as a major stimulus.

Add to that the fear of judgment from a specific audience or other external stresses, and the arousal can quickly reach uncomfortable levels. Over the years, I’ve developed various strategies to manage this, including meditation, breathing exercises, and thorough preparation. Often, I find that once I push through the initial wave of nervous excitement, I can relax into the moment and perform just fine.

But notice this isn’t simply the fear of public speaking or fear of judgment, though those may play a role. The act itself is inherently stimulating—you’re excited about your topic, eager to connect with the audience, and energized by the exchange of energy. These are positive forces that can fuel your performance. If you interpret all this stimulation as fear or something negative, you’re missing the full picture.

Even if you don’t qualify as a Highly Sensitive Person, I encourage you to reinterpret your “fear” of public speaking in this way.

Footnotes

Dr. Elaine Aron’s Website - https://hsperson.com

Aron, Elaine. The Highly Sensitive Person: How to Thrive When the World Overwhelms You. 28. [Nachdr.], Broadway Books, 2010.

Alane Freund’s Google TED Talk: