#8 - An Introvert’s Paradise

How the Pandemic Flipped the Script on Extroverts.

In March 2020, extroverts everywhere got a taste of what it’s like to live in an introvert’s paradise.

Once lockdown began, those of us fortunate enough to have remote-friendly jobs settled into a routine with far more solitude—and zero commute. We wove our personal lives into the day, squeezing in lunch prep, dog walks, quick errands, and tending to the kids, all in exchange for reclaimed commuting time and—let’s be honest—a bit less personal grooming (they can’t smell you over Zoom).

It took some getting used to, to be sure—staring at my own face on Zoom for hours, sitting for long stretches—and I did miss the hallway conversations and lunch breaks with coworkers. But I still talked to people all day on Zoom, with little icebreaker chats sprinkled in. As an introvert, that was enough for me, and I was pretty content with the life I worked out. It also let me be more present for my kids in their last years at home before heading off to college, and I’m deeply grateful for that time.

For my extrovert friends, lockdown ranged from merely unpleasant to truly brutal. Some became clinically depressed. Others—especially those with small children—appreciated certain aspects but struggled with the isolation.

We did our research

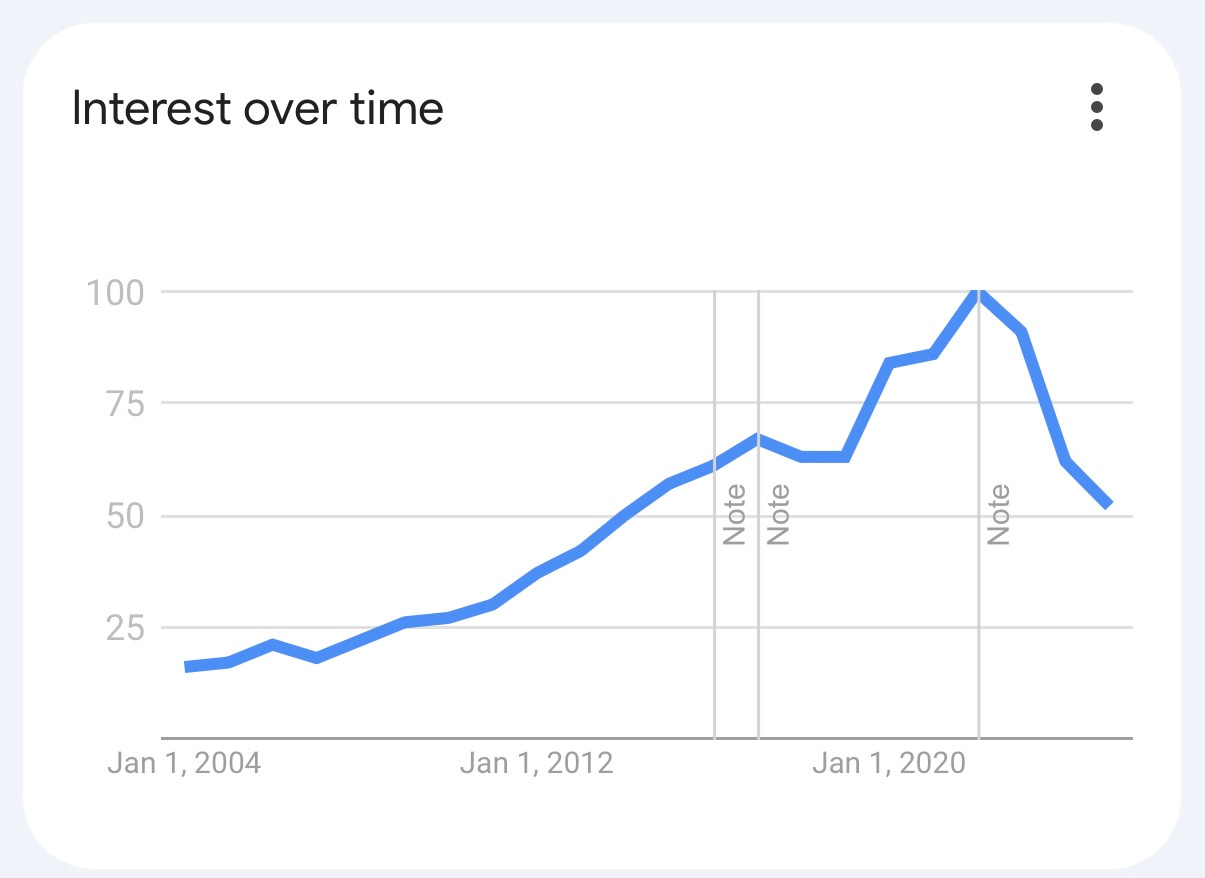

With more time on our hands, many of us became more reflective. We googled all sorts of things—PPE, wet markets, the R₀ of a virus. But one topic stood out: “Introversion and Extraversion.” Nothing like a pandemic to make you confront your feelings about life without constant social interaction.

According to Google Trends, which tracks search term popularity over time, interest in this topic peaked in April 2020—and it didn’t taper off until 2023!

It’s cool to see the steady rise of interest over time, accelerating in the 2010s with the publication of Susan Cain’s Quiet and the spread of her popular TED Talk. But it wasn’t until the pandemic hit that interest skyrocketed to all-time highs.

Beyond giving the world an unwanted crash course in epidemiology, the pandemic did more than anything else to bring widespread awareness to this important personality trait.

More than anything, the pandemic gave extroverts a taste of what it’s like to work in a workplace that isn’t designed for their personality.

For an extreme introvert, navigating a noisy, crowded workplace is about as comfortable as quarantine was for an extreme extrovert. It was a terrible experience for them, but if there was a silver lining, it’s that it created a more universal understanding of why we need more balanced, flexible workplaces.

Many of us liked it

Before the pandemic, my company—like most others—expected us to spend 40+ hours in the office. But when lockdown lifted, that changed. Remote work and hybrid models took hold, at least in tech.

According to a Salon article from November 2024:

79% of tech companies in North America allow employees to decide when they work in the office (56%) or are fully remote (23%). Another 18% have a structured hybrid mandate (specific in-office days), while only 3% are fully in-office.

As the world reopened, many of us discovered that a flexible remote arrangement wasn’t just convenient—it was more pleasant, humane, and productive.

I’ve been fortunate that my company has both a local office and a widely distributed workforce, meaning every meeting is designed to support remote participants. I choose to go into the office 1–2 days a week because I enjoy it and find it to be the right balance. Our remote employees also come in quarterly for planning and team bonding.

For tech companies, this blend of remote and in-person work offers an ideal balance—fostering in-person connections while preserving focus time and flexibility.

This is what it looks like to live in a world that better accommodates a range of personalities.

The pre-pandemic workplace has its roots in the Industrial Revolution. Command-and-control management structures were designed for the military and factory floors—an outdated fit for the digital economy of the 21st century. Yet many leaders still default to this model simply because it’s what they know.

Extroverts shouldn’t be forced into isolation. And introverts shouldn’t have to navigate social hotbeds like the modern office for 40+ hours a week.

Workers should have the choice to work where they are most productive. It’s the most humane, the most logical—and the most profitable—approach. Make people more productive, and they will make you more money. It doesn’t get any more straightforward than that.

[Of course, this argument excludes industries and jobs that must be performed in person, and it won’t fit the culture of every company. But for most white-collar jobs, and much of corporate America, the benefits are undeniable.]

Return To Office (RTO): Turning Back the Clock

My friend Pete works at Amazon. Even as an extreme extrovert—someone who loves nothing more than being surrounded by people all day—he enjoyed his three-day office schedule. It gave him back hours of commute time and let him better support his personal life. But as of January 2025, he’s back in the office five days a week.

Amazon is infamous for its brutal work culture, from warehouse drudgery and union-busting to the cutthroat competition of its corporate offices, where crying at your desk is practically a rite of passage. So it’s no surprise that they’re leading the charge on RTO. What does amuse me, though, is how Google and Meta happily scooped up the furious introverted engineers who quit as a result.

Amazon is a $1.65 trillion mythical beast—that’s what, 1,600 unicorns? What works there isn’t a great model for the rest of the world. Adults can decide for themselves whether that tradeoff is worth it.

Unfortunately, many companies will follow suit, clinging to industrial-era ideas about work and human behavior. And that hurts everyone. Commute time is one of the most egregious wastes of our most precious resource—time—not to mention its environmental cost from increased fossil fuel emissions. Of course, some people feel the pain of these policies more than others… introverts in particular.

What’s the argument for RTO?

The most common rationales I’ve heard from senior leaders and investors center around three things: a loss of company culture, declining productivity, and weakened collaboration.

Spotify takes a different approach, embracing remote work as a core part of its culture and company values. In an October 2024 interview, Katarina Berg, Spotify’s CHRO, put it bluntly:

‘You can’t spend a lot of time hiring grown-ups and then treat them like children… We are a business that’s been digital from birth, so why shouldn’t we give our people flexibility and freedom? Work is not a place you come to, it’s something you do.’

Spotify has seen no drop in productivity or efficiency—arguably the most measurable impact of remote work. And given how many tech companies continue to operate fully remote or hybrid, it’s clear they’re not alone in this.

That said, concerns about remote work’s impact on collaboration and innovation are real. Berg acknowledges:

‘It is harder, and we all struggle to collaborate in a virtual environment.’

To address this, Spotify has partnered with the Stockholm School of Economics to study the long-term effects of remote collaboration.

There’s no doubt that some levels of collaboration are harder to achieve remotely. But the real question is: how often do we actually need that level of in-person collaboration? Spotify, like many others, has shifted its offices into destination spaces where employees can gather when needed, including for mental health and well-being.

At a minimum, they’ve established what they call ‘core week’—one week per year where teams meet in person to discuss strategy and collaborate.

‘By having one week where small teams travel to meet up, we can energize people while keeping our climate impact low,’ Berg explains. ‘It has worked really well.’

Some worse reasons for RTO

Spotify’s Berg already pointed to one obvious reason some leaders push for RTO: a lack of trust in their employees. If management fears being taken advantage of, that’s a symptom of much deeper issues. Do you have the right people for the job? The right support systems to help them succeed? The right incentives in place? Do employees understand why their work matters, and do their managers know how to motivate them?

We now have far better management techniques than in the past. Command-and-control leadership is lazy management. And if it seems easier, that’s because it is—it requires less thought and ingenuity.

If your solution to these challenges is to fall back on methods designed when the steam engine was cutting-edge technology, you’re not just stuck in the past—you’re setting yourself up for spectacular failure in the age of AI.

Here’s a refined version that sharpens the argument, improves clarity, and enhances flow while keeping your strong, direct tone:

An Even Worse Reason for RTO

An even worse reason often cited? Companies’ massive investments in corporate real estate.

Businesses have poured millions into lavish offices—not just as workspaces, but as expressions of their wealth and power. Seeing these status symbols sit empty is the modern-day retelling of The Emperor Has No Clothes. Senior leaders simply cannot admit to making such enormous mistakes or acknowledge the staggering misuse of capital on their books. That kind of failure looks terrible to shareholders.

So, there was no mistake. Employees must return to the office—not because it’s better for them, but because it saves leadership from embarrassment. At least these executives are making their priorities clear. Shame on us if we don’t listen.

If leaders truly understood how to get the best out of their people—by creating a productive work environment that respects personality differences and enables deep focus, deep work, and flow—they’d unlock enormous productivity gains.

Perhaps some of them do realize this. But the short-term optics are too damaging, and the pressure too great, to avoid RTO—at least until they can quietly unwind their real estate investments.

This keeps the bite while making it a bit more polished and impactful. Let me know if you want any adjustments!

The best leaders

In some ways, nothing about this debate is new—it’s been understood since the time of Lao Tzu. The Tao Te Ching offers a relevant passage:

“When the best leaders’ work is done, the people say, ‘We did it ourselves.’

If you do not trust the people, they will become untrustworthy.

The best leaders accomplish their tasks and let the people think they did it themselves.”

Leadership built on trust isn’t just more effective—it creates a workforce that thrives.

Many of us are fortunate enough to have some choice in the leaders we follow. Others may be stuck, at least for a while, in more difficult circumstances.

May you find, surround yourself with, and grow to become the best kind of leader. The world needs you.